The four-part reimagining of Hideaki Anno’s hit series Neon Genesis Evangelion has come to an end, an unapproachable and unforgivingly confusing end.

If you are here for a summary of what you “need to know”, or a recap of the events of Neon Genesis Evangelion before you watch the film, I will candidly let you know it is not worth it. Aside from the eye-catching animation and suitably niche score, there isn’t much in this film for you.

But, even if you’ve even only seen the original Neon Genesis Evangelion, I hope you will watch Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon A Time.

The First, Second, and Third Children. (Evangelion 3.0+1.0)

The Rebuild tetralogy’s strange naming scheme comes to a head in this pop-emo epic, to the point that this films title is predicated upon a metatextual understanding of the franchise. “Thrice Upon A Time” referring to the last two “endings” the series has received so far. The end of the limited run TV series Neon Genesis Evangelion in 1996, and the optimistically titled End of Evangelion in 1997.

The titles derisive finality echoes within the text of the film itself. While I could not in good faith say this movie was written with ill-will toward the franchise (unlike some of its predecessors in the Rebuild franchise), I find the naming convention a useful piece of context for anyone considering watching this film.

The past is essential to Thrice Upon A Time, as the film brings the central themes of the Evangelion franchise back to the forefront. Nostalgia, the naval gazing “Hedgehog’s Dilema”, and the series’ meditation on trope are elevated to the forefront, as Hideaki Anno brings his franchise to a close.

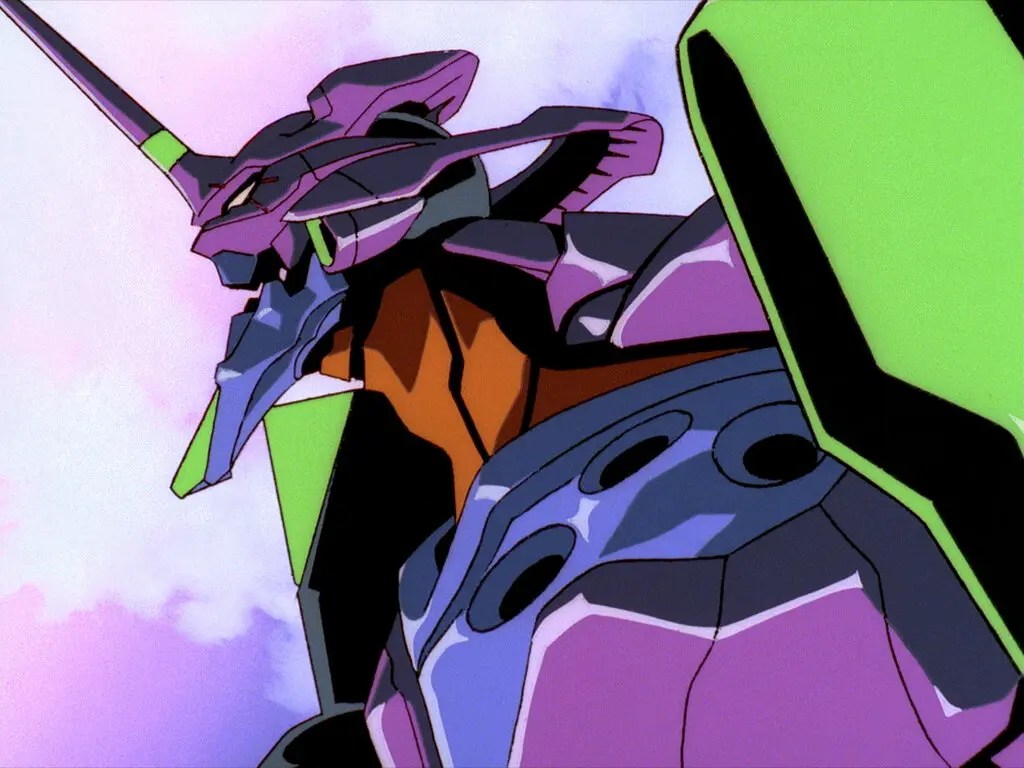

The Near Third Impact (Evangelion 2.22)

Importantly, unlike the prior entry in the Rebuild franchise (the critically panned and highly contentious Evangelion 3.33: You Can (Not) Redo), Thrice Upon A Time grants its viewer reprieve from the harsh world created by Evangelion 2.22’s major diversion from the limited-run TV series, Shinji’s early activation of the Third Impact (the climactic result of an Evangelion interacting with Lillith).

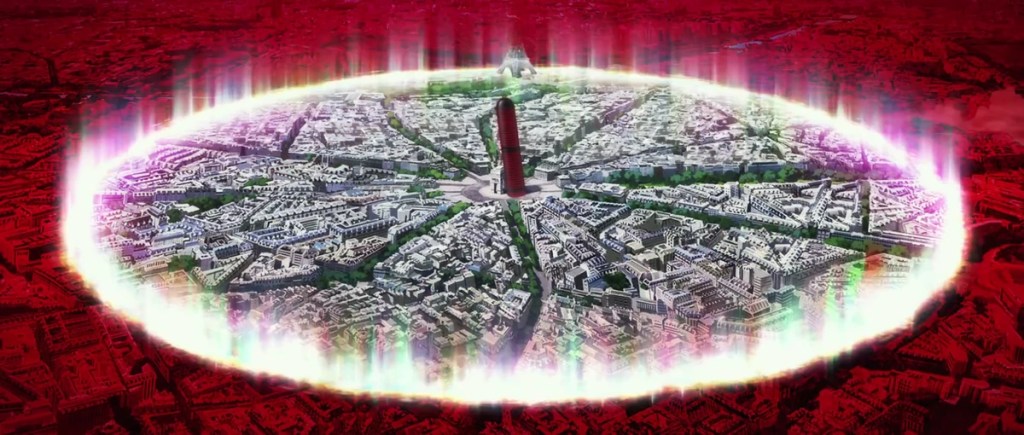

Thrice Upon A Time film opens in a similar fire and lightning fashion to its predecessor, with a battle featuring the newest Eva pilot, Mari. But, unlike the technicolor, spacefaring opening of Evangelion 3.33: You Can (Not) Redo, Thrice Upon A Time grounds itself in the city of Paris, and introduces an essential mechanic to the functions of the poorly explained “Post-Near Third Impact” world Evangelion 3.33 so unceremoniously dropped us within. The damage caused by Shinji’s actions can be undone.

The ruined infrastructure of Paris, restored. (Evangelion 3.0+1.0)

This sequence is immediately intercut with the journey taken by the central three pilots of the franchise, Rei, Shinji, and Asuka, as they begin their journey across the irradiated and destroyed planet to reach a similar zone of protection. A zone of protection which hosts the side characters of the original series, Shinji’s best friends Toji and Kensuke, and Asuka’s good friend, the class rep Hikari.

This reintroduction of stakes, both personal and tangible, grounds Thrice Upon A Time. Consequently, it is at this point that the pacing of the film slows, and the focus shifts to a highly underrepresented character, Rei Ayanami.

Rei’s Smile (Neon Genesis Evangelion)

At the center of Rei’s writing and characterization issues is the trope she was constructed to acknowledge. Rei is meant to be Shinji’s Oedipal fixation, a clone of his mother, constructed without personality, who will do whatever she is ordered to do. As Anno put it, “At the end Rei says “I don’t know what to do,” and Shinji says, “I think you should smile,” and Rei smiles. …In short, if she and Shinji completely “communicated” there, then isn’t she over with? At that moment, Rei, for me, was finished.” Keep in mind, the moment he’s referring to is within Episode 6 of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

In Thrice Upon a Time, Rei is put through a great deal of scrutiny, both metatextual, and by the characters within the film. This iteration of Rei has no name, as she has no desire to select one. She has no opinions, as she has no desire to form any. In all essence, she is nearly identical to the Rei presented in the original series. Asuka, in the first major reveal of the film, even vengefully tells Rei that her empathy for Shinji is pre-programmed in, like the personalities of each of the Children.

Except Rei begins to change, because she’s given the time to change. In a severe and heartwarming sequence, we spend fifteen minutes of runtime witnessing Rei’s personal growth. How, despite being an inhuman character, the focus of a community and the very film itself alters Rei beyond recognition. In Thrice Upon a Time, each of the central cast members, is treated with this same level of care.

Asuka Piloting Unit 2 (Evangelion 3.0+1.0)

Instead of retreading the already established backstory and emotional turmoil of Asuka’s character, she is given a completely new emotional center for Thrice Upon a Time. Asuka has inhabited this world in the ~14 years between the second and third Rebuild films, and unlike the conveniently carbonite-frozen Shinji or the clone Rei, has had to experience the full effect of the “Curse of Eva”. A curse upon any pilots of Evangelion, which keeps their body from aging beyond the point that they first entered an Evangelion.

This invention could stem, of course, from money. Per a panel discussion from 2006, the Evangelion franchise is worth at least two billion dollars. Keep in mind, this is from before any of the Rebuild franchise’s films or merchandizing had released. There is value in maintaining a consistent look for the pilots, whose recognizable designs are seen throughout all sorts of merchandizing (statues, t-shirts, etc.)

However, the Curse of Eva also could reflects Anno’s personal feelings about the franchise’s “otaku” culture that has sprouted since its release. Otaku, referring to the dedicated group of people obsessed with anime-pop-culture, often at the detriment of their social skills. After all, Evangelion, despite being deeply entrenched in subversive ideas for the genre, is still a billion dollar mecha franchise with 14-year-old pilots in scantily-clad jumpsuits fighting—for all intents and purposes—aliens.

Hideaki Anno (2021)

Anno, especially after the actionless conclusion of the TV Series, lamented the shows status in “otaku” culture often. Saying in one interview, “Otaku only know the world of the otaku. I’m the same way…But when I feel that my own standards have reached their limits, I have no choice but to compare them with the standards of others and correct the errors.” Directly comparing his isolationist, lonely philosophy (presented within the show as the “Hedgehog’s Dilema”) to otaku culture. But notably, he distinguishes himself from otaku, by his ability to change.

Asuka similarly laments on her curse, and considering the severely over-sexualized merchandizing of her character in particular, its not hard to see the connection between the two. Where Anno found his disdain for otaku culture was the inability to change, the consumerist nature of otaku means that a franchise cannot change. As changing could evoke the wrath of people who have dedicated their time, finances, and personal feelings towards a series, and feel they are owed something in return. This means our characters cannot change, such is the Curse of Eva.

Shinji (Evangelion 3.0+1.0)

Unlike Anno’s first end of Evangelion, Thrice Upon a Time puts on the horse and pony show. The film lights itself ablaze with uniquely choreographed and visually intense action sequences. With it’s clearly explained stakes and character, Thrice Upon A Time avoids losing itself within the tempting psychopomp of the Third Impact sequences, distinguishing itself plenty from the TV ending.

Unlike Anno’s second End of Evangelion, Thrice Upon a Time doesn’t have to worry itself with tonal consistency or impact. The franchise is so massive, so relentless, that at this point, tonal consistency is a foregone conclusion. While End of Evangelion is the perfect send-off to the series that Neon Genesis Evangelion was, it couldn’t even hope to address what the Evangelion franchise has since become. Thrice Upon a Time steps up in that regard.

Anno’s third ending to the franchise is an all-encompassing masterclass in metatext. Thrice Upon a Time releases both its cast of characters and its creator from the Sisyphean endeavor of maintaining a franchise. And to return to the guise of a review for one moment, yes, I recommend Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon A Time.

Leave a comment